Sunday Jazz Launches Spotify Playlist

You can now find the program’s selections on Spotify.

You can now find the program’s selections on Spotify.

Jazz icon Thelonious Monk once said “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

Sometimes the music’s so good, you can’t help but dance.

On April 22, for Record Store Day 2017, Resonance Records will release for the first time ever, Thelonious Monk’s complete 1959 studio recordings made for the French film “Les Liaisons Dangereuses.”

The cover alone gives us goosebumps.

“Thelonious Monk’s soundtrack to Les liaisons dangereuses, the provocative French film directed by Roger Vadim, will be released as a double album this spring. Arriving in a year of centennial tribute to Monk, the genius pianist and jazz modernist, it registers as a fresh discovery: while this music was recorded in 1959, it has never been available outside the context of the film, which is out of print.” – NATE CHINEN at wbgo.org (read their whole piece HERE)

You can listen to the track “Rhythm-a-Ning,” courtesy of wbgo.org, HERE.

Two Tenors: L-R Charlie Rouse & Barney Wilen

The session for the record took place at Nola Penthouse Sound Studios on West 57th Street in New York, in the summer of ’59. The group is Monk’s working Quartet of the time, with his right arm, tenorman Charlie Rouse, along side bassist Sam Jones and legendary drummer Art Taylor. The twist here is that French tenor player Barney Wilen joins in as well. Wilen, only 23 years old at this point, is less known to American audiences, but a great player, well respected in his time and leader on a number of classic sessions. And good enough to get studio time with the High Priest himself.

By now you probably know about Record Store Day – “an annual event inaugurated in 2007 and held on one Saturday every April to celebrate the culture of the independently owned record store.” Record labels distribute store-only copies of special releases, encouraging fans to get offline and back into brick & mortar shops. It’s worked in a lot of ways. And while some releases feel a little forced, some are pretty exciting. Never-before-heard live recordings, or demos or long-out-of-print albums being brought back to light.

This early Modern Jazz Quartet LP on Savoy Records was re-released for RSD 2016

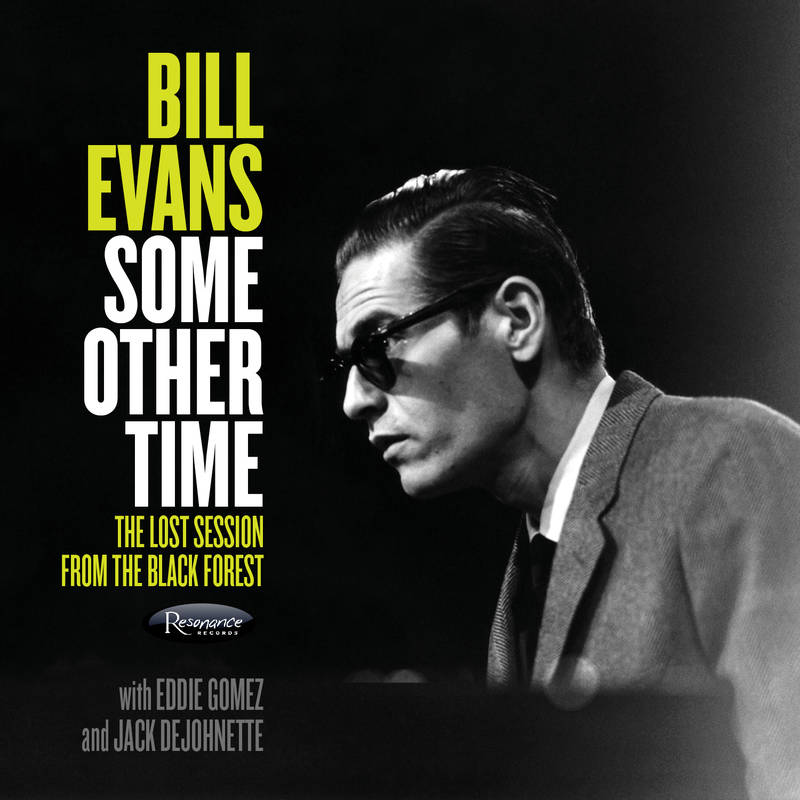

For us jazz fans though, Record Store Day can often feel pretty damn thin. There’s been some cool stuff over the years. Curtis Fuller’s “Blues-Ette” on Savoy a few years ago is one that flew under a lot of people’s radar, and it’s a brilliant album; one of the best of the 50’s (there’s still plenty of copies floating around locally, for cheap). The Coltrane 10″ of Roulette recordings last year was cool, if a bit short. The Charlie Parker Story was an essential you need for your jazz library. If you were lucky or smart enough to get a vinyl copy of Resonance Records’ absolutely brilliant Bill Evans release, “Some Other Time,” a previously unreleased studio recording from 1968, you’re doing good on margin. The LP retailed for around $35 on RSD. Currently on discogs.com, a near-mint copy can be had for around $200 or more. So some of these are just good value-plays. (The 2xCD copy can be easily had for cheap on Amazon, and it is absolutely worth it, KTRU Sunday Jazz-approved).

A lost studio recording by the 1968 version of the Bill Evans Trio, arguably one of the finest jazz releases in years.

But what made that Evans release so special in the end, were a few factors:

1) An important, even iconic artist

2) A full-length studio recording – not a poor quality live show bootleg – but studio quality recordings. Hi-Fidelity.

3) Never-Before-Heard until now. Music that even the most ardent fans, haven’t yet heard.

The Evans release was special. We just don’t get these kinds of treats very often.

It’s these same factors that make the news of the new Thelonious Monk release so exciting.

Monk in the studio slugging a cold beer, with his dear friend and muse, Pannonica de Koenigswarter (center)

While the Record Store Day LPs will surely disappear quickly, the CD is scheduled for wide release this May.

We will be watching the clock waiting for one more month to pass. But in the meantime, here’s some Monk to help get you through the week:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=twriNk0N9qQ

The Jazz Documentary. Sometimes, there’s nothing more glorious to a jazzhead. There’s so many to choose from. Essentials that come to mind include the Clint Eastwood produced, absolute classic, “Thelonious Monk: Straight No Chaser,” the mellow and avant-garde black and white beauty of Bruce Weber’s “Let’s Get Lost” on Chet Baker, “A Joyful Noise,” Robert Mugge’s 1980 look at Sun Ra & The Arkestra. Or the tragic look at the tale of Joe Albany: “A Jazz Life.”

Right now is an incredibly exciting time for jazz fans. The word is out on Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” a documentary on the tragically-short life of Lee Morgan. The film is making the rounds on the festival circuit currently and reviews are more than encouraging – the buzz is real:

After years of collective head-scratching by jazz fans wondering what the hold-up was, someone has finally made a definitive documentary on the life and music of Bill Evans; arguably the most influential jazz piano player of all-time and certainly of the post Monk-Powell era. Behind a paywall, it can be screened HERE.

And though other films have covered him, there’s considerable anticipation for the forthcoming “Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary.”

““I just thought…oh my god…you know this guy, in his mind, and his heart, his soul, they’re in a place that everybody oughtta reach for.”

— President Bill Clinton on hearing John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme album.

With all this in mind, while reading the new interview by the fantastic team at Dust & Grooves – a piece discussing record collecting with visual artist/model/fellow record nerd Logan Melissa (insta: @heightfiveseven), another Jazz Doc gem was discussed, one we had forgot existed, and subsequently ran to YouTube for.

Logan Melissa on Dust & Grooves – talking Jackie McLean

Luckily, it was there.

Directed by Ken Levis, “Jackie McLean On Mars” is a 1979/80 short film, looking at the life and work of the great alto player.

McLean’s story is in many ways the story of jazz in the middle of the 20th century.

“McLean was born in New York City. His father, John Sr., played guitar in Tiny Bradshaw’s orchestra. After his father’s death in 1939, Jackie’s musical education was continued by his godfather, his record-store-owning stepfather, and several noted teachers. He also received informal tutoring from neighbors Thelonious Monk, Bud Powell, and Charlie Parker. During high school he played in a band with Kenny Drew, Sonny Rollins, and Andy Kirk Jr. (the tenor saxophonist son of Andy Kirk).

Along with Rollins, he played on Miles Davis’ Dig album, when he was 20 years old. As a young man McLean also recorded with Gene Ammons, Charles Mingus on the seminal Pithecanthropus Erectus, George Wallington, and as a member of Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. McLean joined Blakey after reportedly being punched by Mingus. Fearing for his life, McLean pulled out a knife and contemplated using it against Mingus in self-defense. He later stated that he was grateful that he had not stabbed the bassist.” (wikipedia)

McLean would have been a legend had he never made it to the 60s. His recordings as a sideman and a leader for labels like Jubilee and Prestige would have cemented a strong legacy. But as the 60s came on, he never settled in his ways. He became a leader of the “New Thing” developed by players like Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane. Like so many of his peers, he battled a heroin addiction.

In a crowded field of post-Bird alto-players, McLean managed to create an immediately recognizable tone; his sharp-notes swinging and stabbing like a butterfly knife. His output for the Blue Note label remains highly sought-after by collectors as some of the great moments in the storied label’s catalog.

He continued into the 70s and 80s, recording for SteepleChase Records in Europe, East Wind in Japan and more.

In 2000, he recorded one more record for Blue Note, the critically acclaimed “Nature Boy.”

It’s a good time to be a JazzHead. Great films to watch and never a shortage of new records to find. Here’s to Jackie.

Jazz For Your Thursday.

Join us on Sundays for KTRU SUNDAY JAZZ. Every week at 2pm central on 96.1 FM Houston and live online at KTRU.org.

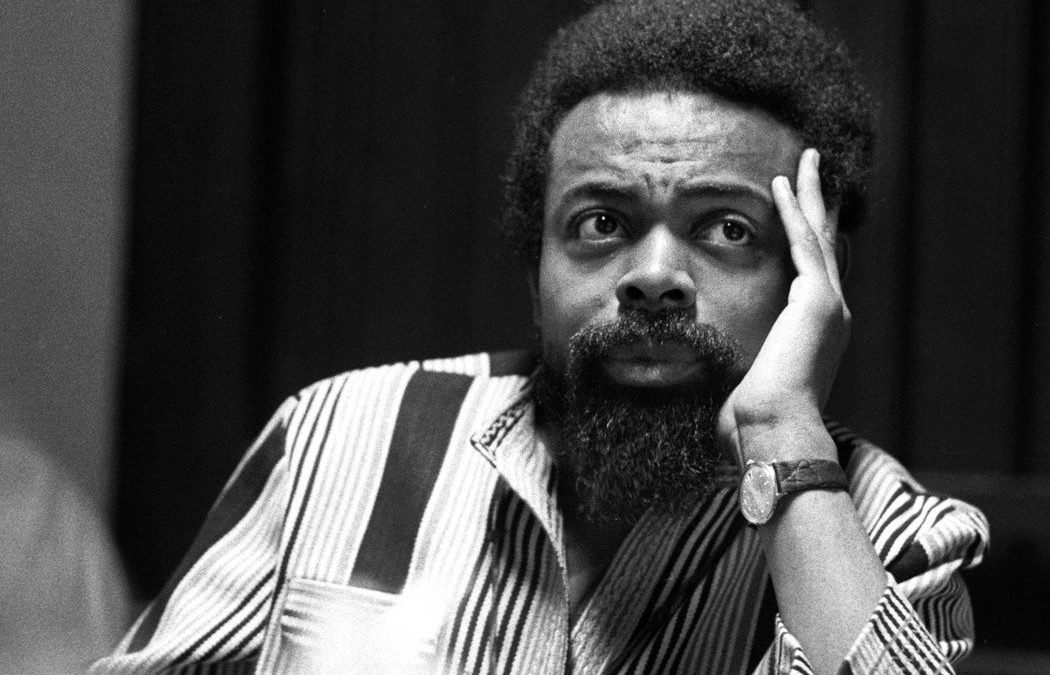

(Amiri Baraka: poet, author, historian and music critic)

The essay below was found in a blogpost from Open Sky Jazz. We are unsure of where it was originally published. In an attempt to share exciting and thought-provoking content furthering discussions on this music we love, the KTRU Sunday Jazz team will continue to share the good stuff we find and enjoy from the web and beyond. We have added pictures and numerous links to songs and visual aids to add to the experience of the piece. Click on the links! And enjoy.

What Amiri Baraka Taught Me About Thelonious Monk

(Thelonious Monk at the piano)

“Monk was my main man.” – Amiri Baraka

I just spent the past fourteen years of my life researching and writing a biography of pianist/composer Thelonious Monk, and over thirty years attempting to play his music. My obsession with Monk can be traced back to many things and many people, but paramount among them is Amiri Baraka. Let me explain.

My path to “jazz” began like so many others of my generation who came of age in the late 1970s — with the funky commercial fusions of Grover Washington, Jr., Bob James, Patrice Rushen, Earl Klugh, Ronnie Laws, through Stanley Clarke and Chick Corea. But inexplicably, at the tender age of seventeen or eighteen I took a giant leap directly into the so-called “avant-garde”, or the New Thing. By 1980, the New Thing wasn’t so new (and as Baraka and others have shown us, it wasn’t so new in the 1960s), but the music appealed to my rebellious attitude, my faux sense of sophistication, and to the way I heard the piano. As a young neophyte piano player and sometimes bassist, my heroes became Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Archie Shepp, late ‘Trane, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, those cats. I knew almost nothing about bebop, nor could I name anyone in Ellington’s orchestra except for Duke. I just thought free jazz was the beginning and end of all “real” music. My stepfather introduced me to Charlie Parker, Monk, Bud Powell, Dexter Gordon, but I wasn’t yet ready to fully appreciate bebop. Then in one of my many excursions to “Acres and Acres of Books” in Long Beach, California, I picked up two used paperbacks by one LeRoi Jones: Blues People and Black Music.

I dove into Black Music first. Imagine my surprise when I discovered a thoughtful piece on Monk in a book that I understood then to be a collection of essays primarily about the “New Thing.” Don’t get me wrong; I dug Monk from the first listen. I had heard an LP recorded live at the Five Spot Cafe with Monk and tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin. I wore it out, especially their rendition of Monk’s “Evidence”. But Monk wasn’t part of the jazz avant-garde. He was already an old man when Ornette Coleman made his debut, or so I thought. Baraka’s Black Music corrected me, schooling me on the roots and branches of free jazz. Between his piece on “Recent Monk,” his brilliant treatise, “The Changing Same (R&B and the New Black Music),” and several other pieces on white critics and the jazz avant-garde, I began to hear Monk and “free jazz” quite differently. It was Baraka who dubbed the jazz avant-garde the “New Black Music,” insisting that it emerged directly out of a Black tradition, bebop, as opposed to the Third Stream experiements of Gunther Schuller, Lee Konitz, and Lennie Tristano. While Black musicians might have milked Western classical traditions for definitions and solutions to the “engineering” problems of contemporary jazz, Europe is not the source. “[J]azz and blues,” he writes, “are Western musics; products of an Afro-American culture.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZZwKtBLO-zw

Of the few hundred times I listened to Monk, Johnny Griffin, drummer Roy Haynes, and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik tear the roof off the Five Spot, I probably heard Baraka, shouting his approval and urging them on from his table near the bandstand. It was August of 1958 and Baraka (when he was still LeRoi Jones) had been an East Village resident for the past year. He became a Five Spot regular when Coltrane was with Monk in the summer and fall of 1957. His constant presence gave him unique insights into Monk’s music and the challenges it created for the musicians who played with him. Indeed, Baraka was one of the few critics to admit that “opening night [Coltrane] was struggling with all the tunes.” Baraka just didn’t come to dig the music, he studied Monk.

((L-R: Thelonious Monk, Jewels Colomby(?), TS Monk, Amiri Baraka (taking picture) and Ran Blake))

In fact, he was arguably the first American critic, along with Martin Williams, to really understand what Monk was doing and why a new generation of self-described avant-garde musicians was drawn to Monk’s music and his ideas. By the time Baraka entered the fray, most critics had either dismissed Monk for having no technique or formal training as a pianist, or they praised him for his eccentricity and inventiveness precisely for his lack of technique or formal training. For Baraka, the whole issue of Monk’s technique was nonsense: “I want to explain technical so as not to be confused with people who think that Thelonious Monk is ‘a fine pianist, but limited technically.’ But by technical, I mean more specifically being able to use what important ideas are contained in the residue of history or in the now-swell of living. For instance, to be able to double time Liszt piano pieces might help one become a musician, but it will not make a man aware of the fact that Monk was a greater composer than Liszt. And it is the consciousness, on whatever level, of facts, ideas, etc., like this that are the most important parts of technique.”

While Baraka’s fellow Beat generation writers embraced Monk because they heard spontaneous, instinctual feeling and emotion as opposed to intellect, Baraka saw no such opposition; he was careful not to divorce consciousness and intellect from emotion. He writes, “The roots, blues and bop, are emotion. The technique, the ideas, the way of handling the emotion. And this does not leave out the consideration that certainly there is pure intellect that can come out of the emotional experience and the rawest emotions that can proceed from the ideal apprehension of any hypothesis.” Like his insights about Monk’s technique, the point underscored Baraka’s general claim that bebop was roots music, no matter how deep the imperative for experimentation, because it carries deep emotions, historical and personal. The music of the Blues People.

(Baraka)

And if Thelonious Monk was anything, he was Blues People. Born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the grandson of enslaved Africans, delivered by a midwife who was thirteen when Emancipation Day came, Monk was raised by parents who grew up picking cotton and survived on odd jobs and cleaning white folks’ homes. His mother brought Thelonious and his two siblings to New York in search of a better life, and while they enjoyed more opportunities the Monks settled in the poor, predominantly black neighborhood of San Juan Hill (West 63rd Street, Manhattan). Thelonious grew up listening to the blues, jazz, the rhythms of calypso and merengue, hymns and gospel music (he spent two years traveling through the Midwest with an evangelist). His mother Barbara, scrubbed floors to pay for his classical piano lessons, and Monk continued his studies under the tutelage of the great Harlem stride pianists of the day. Monk told pianist Billy Taylor “that Willie “The Lion’ and those guys that had shown him respect had… ’empowered’ him… to do his own thing. That he could do it and that his thing is worth doing. It doesn’t sound like Tatum. It doesn’t sound like Willie ‘The Lion’. It doesn’t sound like anybody but Monk and this is what he wanted to do. He had the confidence. The way that he does those things is the way he wanted to do them.”

Willie ‘The Lion’ never mentions Thelonious in his memoirs, but he described the all-night cutting sessions which sharpened Monk’s piano skills: “Sometimes we got carving battles going that would last for four or five hours. Here’s how these bashes worked: the Lion would pound the keys for a mess of choruses and then shout to the next in line, ‘Well, all right, take it from there,’ and each tickler would take his turn, trying to improve on a melody… We would embroider the melodies with our own original ideas and try to develop patterns that had more originality than those played before us. Sometimes it was just a question as to who could think up the most patterns within a given tune. It was pure improvisation.” A later generation of bebop pianists would often be accused of one-handedness; their right hands flew along with melodies and improvisations, while their “weak” left hands just plunked chords. A weak left hand was one of Smith’s pet peeves among the younger bebop piano players. “Today the big problem is no one wants to work their left hand — modern jazz is full of single-handed piano players. It takes long hours of practice and concentration to perfect a good bass moving with the left hand and it seems as though the younger cats have figured they can reach their destination without paying their dues.”

(Willie “The Lion” Smith)

Teddy Wilson, though only five years older than Monk but considered a master tickler of the swing generation, had nothing but praise for Thelonious’s piano playing. “Thelonious Monk knew my playing very well, as well as that of Tatum, [Earl] Hines, and [Fats] Waller. He was exceedingly well-grounded in the piano players who preceded him, adding his own originality to a very sound foundation.” Indeed, it was this very foundation that exposed him to techniques and aesthetic principles that would become essential qualities of his own music. He heard players “bend” nots on the piano, or turn the beat around (the bass note on the one and three might be reversed to two and four, either accidentally or deliberately), or create dissonant harmonies with “splattered notes” and chord clusters. He heard things in those parlor rooms and basement joints that, to modern ears, sounded avant-garde. They loved to disorient listeners, to displace the rhythm by playing in front or behind the beat, to produce surprising sounds that can throw listeners momentarily off track. Monk embraced these elements in his own playing and exaggerated them.

Finally, Baraka was one of the first critics to predict that Monk’s long awaited success in the early 1960s might negatively impact his music. Indeed, this was the point of his essay, “Recent Monk.” Thelonious’s fan base had expanded considerably after he signed with Columbia Records, made a couple of international tours, and appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in 1964. But Baraka noted that Monk’s quartet, like so many successful groups, began to fall into a routine that sometimes dulled the band’s sense of adventure. Baraka warned, “once [an artist] had made it safely to the ‘top,’ [he] either stopped putting out or began to imitate himself so dreadfully that early records began to have more value than new records or in-person appearances… So Monk, someone might think taking a quick glance, has really been set up for something bad to happen to his playing.” To some degree, Baraka thought this was already happening and he placed much of the blame on his sidemen. Of course, Monk hired great musicians during this period — Charlie Rouse (tenor sax), bassists Butch Warren and Larry Gales, and drummers Frankie Dunlap and Ben Riley. But the repertoire remained pretty much the same, and the fire slowly dissipated. Monk himself continued to play remarkably, but there was an element of predictability that overrode all the amazing things he was doing. “{S}ometimes,” Baraka lamented, “one wishes Monk’s group wasn’t so polished and impeccable, and that he had some musicians with him who would be willing to extend themselves a little further, dig a little deeper into the music and get out there somewhere near where Monk is, and where his compositions always point to.”

(Monk on the cover of TIME magazine, February, 1964)

Baraka never gave up on Monk, and while I can’t prove it I suspect Monk’s music continues to have a strong philosophical and aesthetic influence on both his literary and political work. But more than anything, I will always be grateful to Baraka for helping me discover Monk, for revealing that Monk’s rootedness in this history, in family, in tradition explains why his music, as modern as it is, can sound like it’s a century old. It explains why he always remained a stride pianist; why his repertoire was peppered with sacred classics like “Blessed Assurance” and “We’ll Understand it Better, By and By”; and why the careful listeners can hear in Monk’s whole-tone runs, forearm clusters, unusual tempos and spaces, shouts, field hollers, the rhythm of a slow moving train, rent parties, mourners, children playing stickball and marbles, and the Good Humor or Mr. Softee truck on a summer evening.

Like most scholars and other voyeurs, we are always listening for, and looking at, art for personal tragedy rather than collective memory, collective histories. Amiri Baraka understood the fallacy of this approach. Perhaps this is why he writes in the poem “Funk Lore” (one of several associated with Monk):

That’s why we are the blues

Ourselves

That’s why we

Are the

Actual

(Amiri Baraka, formerly known as Leroi Jones)

END

To reiterate, the piece above was written by author Robin D.G. Kelley. His biography of Thelonious Monk is a contemporary classic and is considered an essential for the jazz bookshelf by the KTRU Sunday Jazz team. The book is available at Amazon.

(Author Robin D. G. Kelley)

KTRU Sunday Jazz airs every Sunday at 2pm central on 96.1 FM Houston and live online at ktru.org.

Standing With Giants

(L-R: Horace Silver, Pee Wee Marquette, Curly Russell, Art Blakey, Lou Donaldson and Clifford Brown)

Mosaic Record’s Daily Jazz Gazette consistently has some great content for jazz head’s in need of a good read. This blogpost was taken in full from their site, which appears to have originally appeard on a blog called DangerousMinds dot net. The KTRU Sunday Jazz Team felt compelled to share this one for a Monday.

‘HALF A MOTHERFUCKER’: THE LEGEND OF PEE WEE MARQUETTE

Pee Wee Marquette and Count Basie

Pee Wee Marquette is another of those characters who, like Moondog, found a niche in New York’s cultural ecosystem and carved out a life for himself “back in the day.”

It was not probably what you’d call a very good life, but, what the hell, he’ll remain a sort of Jazz legend long after we’re all forgotten. Pee Wee was the 3 foot 9 inch announcer and MC at Birdland, the famous NYC nightclub, and can be heard on the intros to countless classic live Jazz records from the 50s and 60s.

There’s even a complete CD that came out in 2008 consisting of nothing by Pee Wee’s intros, which are made all the more entertaining by Pee Wee’s deliberate mispronunciation of the names of key acts. You see, Pee Wee would pretty much make life miserable for Jazz acts at Birdland unless they paid him a “tip.” Thus, Horace Silver was “Whore Ass Silber” until Silver relented and paid ($5 in the later years, which was a lot for that time).

The diminutive, but cantankerous, Pee Wee would elbow a non-payer in the groin, blow cigar smoke in their faces, and do even less pleasant things (like telling Bobby Hutcherson to “pack your stuff and get on out of here, we don’t need you”). For this and other reasons he was dubbed by his “pal” Lester “Prez” Young as “half a motherfucker.”

According to legend (and I don’t think this story is on the Internet anywhere), trombonist Bill Watrous once caught up with Pee Wee, who was working the door of the Hawaii Kai restaurant on Broadway in his later years (dressed in a turban and a Nehru jacket, he’d stand outside and try to rustle up paying customers). Watrous saw Pee Wee getting dressed down by some tough guy, claiming that all sorts of harm would befall Pee Wee unless Pee Wee repaid the money he owed or whatever that matter entailed. Watrous saw the tough guy turn to leave and make for the stairs and then saw Marquette run over and stab the toughie in the ass several times with a switch blade before returning to his post, acting as if nothing had happened.

In the book Take Five: The Public and Private Lives of Paul Desmond, Mort Lewis, one-time manager of the Dave Brubeck Quartet recalled Marquette:

There was a black midget, Pee Wee Marquette, who was the master of ceremonies at Birdland. And every act that played there, the musicians had to give him fifty cents and he would announce their names as he introduced the band. Dave Brubeck gave him fifty cents, Joe Dodge gave him fifty cents, and Norman Bates gave him fifty cents. Paul Desmond refused to pay one cent. And when Pee Wee Marquette would introduce the band, he’d always say, in that real high-pitched voice, “Now the world famous Dave Brubeck Quartet, featuring Joe Dodge on drums, Norman Bates on bass,” and then he’d put his hand over the microphone and turn back to Joe or Norman and say, “What’s that cat’s name?” referring to Paul. Then he would take his hand off the microphone and say, ‘On alto sax, Bud Esmond.’ Paul loved that.

Some have questioned whether Marquette was actually female, and just passed as a male, but I’m pretty sure that, had that been the case, it would have made it into the legend somehow or another. Plus, his voice sounds distinctly male to my ears. Interestingly, Pee Wee was interviewed in the mid-80s by David Letterman, so somewhere out there there’s video of William Crayton “Pee Wee” Marquette, telling stories of the old Birdland from his point of view, but (Internet scrub that I am) I wasn’t able to find it.

A compilation of Pee Wee Marquette’s exuberant Birdland intros:

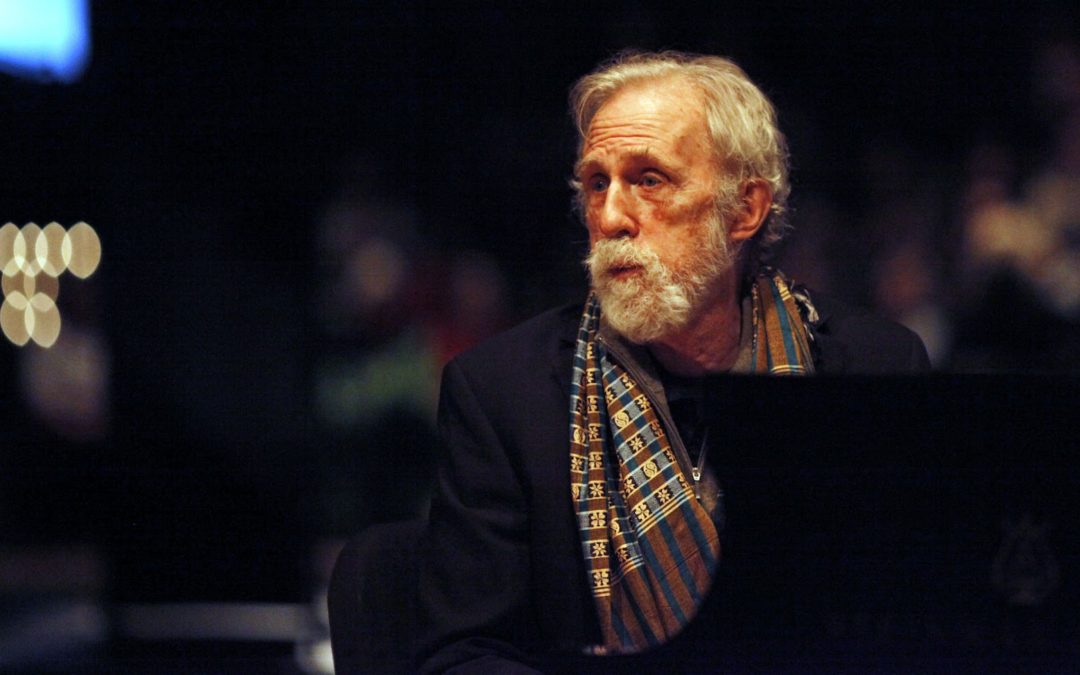

Pianist Ran Blake is coming to Houston.

The avant-garde/Third Stream legend, whose name has been well known in jazz circles since the mid-50’s, will be performing this Saturday, January 7 at the Live Oak Friends Meeting House, at 1318 West 26th St, HTX. Doors open at 4:30pm. Concert begins at 5pm (on time) in order to coincide with the sunset and James Turrell’s Skyspace. Admission is FREE. For more info visit Nameless Sound here.

Sunday Jazz Show DJ Achim will be there and he is VERY excited. He would not miss it.

Some background from Wikipedia, with musical/visual aids from your friends at KTRU Sunday Jazz:

“Beginning in the late 1950s, Blake was part of a duo with vocalist Jeanne Lee. Together they recorded his first album The Newest Sound Around, which was released on RCA in 1962…The album shows Blake’s signature style beginning to develop, as they paid homage to Blake’s early influences with a tribute to David Raksin’s “Laura” and a reworking of the gospel standard, “The Church on Russell Street”.” (wikipedia)

“Blake met Gunther Schuller in a chance encounter at Atlantic Records in 1959. Recognizing Blake’s talent, Schuller asked him to study at the School of Jazz in Lenox, Massachusetts.

Blake met jazz pianist, composer, and arranger Mary Lou Williams during a performance at The Composer, a New York nightclub. She later became a mentor and a significant influence on his work. During his time as a student at Bard, Blake often traveled to see Williams perform and to take lessons from her. Later, Williams and Blake worked together while she was a visiting faculty member at the School of Jazz.” (wikipedia)

“In 1966, Blake released his first record as a soloist, Ran Blake Plays Solo Piano, on New York-based label ESP Disk.

In 1967, Schuller, president of the New England Conservatory, recruited Blake to fill a faculty position as the Conservatory’s Community Services Director. In this position, Blake was responsible for putting on concerts in prisons, retirement homes, and community centers. Blake remained in this role until 1973, when he took on the chairmanship of the new Third Stream Department (now Contemporary Improvisation) at the New England Conservatory, an initiative he started with Schuller.

Schuller coined the phrase “Third Stream” in 1957 during a talk at Brandeis University. According to Schuller, Third Stream is “a new genre of music located about halfway between jazz and classical music”. This new genre was created, in Schuller’s opinion, to combat purists in both the jazz world and the classical world: to play Third Stream music, one had to be proficient in both. When Schuller met Blake, two years after creating Third Stream, Blake’s blend of influences, from free form jazz and gospel music to classical composition and film noir soundtracks, appealed to him. When the two of them created the new department at the NEC, it was natural that Blake would be the chairman. He remained in that position until 2005. He is still a faculty member at the New England Conservatory.

Musicians Don Byron, Matthew Shipp, John Medeski, Grayson Hugh and Yitzhak Yedid have studied with Blake at NEC. He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for composition in 1982, and a MacArthur Genius Grant six years later. At the NEC, he teaches composition classes, as well as a seminar on performance and a special class on film noir, his earliest inspiration.

He has collaborated with a number of other musicians, including Jaki Byard, Houston Person, Steve Lacy, Clifford Jordan and Christine Correa.” (Wikipedia)

Hope to see you there!

Be sure to tune in on Sunday.

KTRU Sunday Jazz airs every Sunday, from 2 to 7 p.m. central, on 96.1 FM Houston and live online at ktru.org.

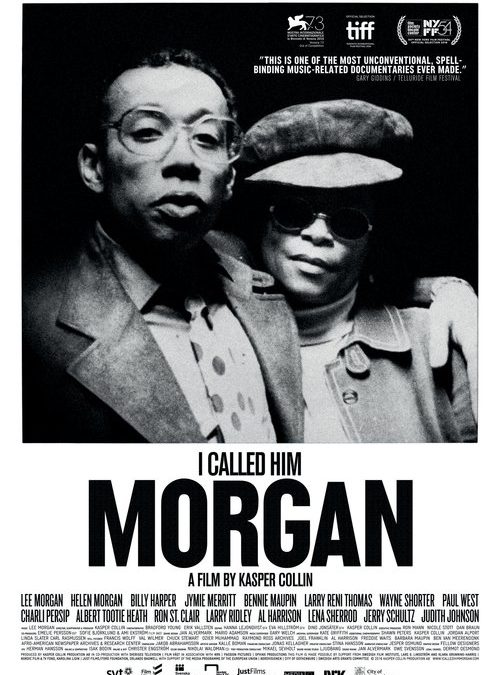

Jazzheads everywhere rejoice – a Lee Morgan documentary is here.

The life and death of the prodigious trumpeter who never made a bad album is chronicled in the new documentary “I Called Him Morgan” (2016), directed by Kasper Collin.

Some may have seen Collin’s last documentary, “My Name Is Albert Ayler” (2006) (though a quick scan of the internet pulls up next to nothing as far as clips or trailers, though apparently it does exist).

But we do have a clip from I Called Him Morgan! Check it out below!!

When and where Houstonians can see it is a bit of a mystery. We’ll update if and when and how, if we can…

But rest easy knowing that this is a film that exists in the world. And it’s getting great reviews!

As a bonus, here’s the YouTube video that, according to an interview, inspired the director to return to the jazz well for his latest documentary:

Happy Birthday to Art Blakey!

“The guru of hard bop, whose famous technique — frequent, high volume snare with bass drum accents — made him one of jazz’s all-time best messengers.”

As the leader of the Jazz Messengers, Blakey earned a reputation as a mentor for some of the greatest talent in the history of jazz – from Benny Golson and Lee Morgan, to Freddie Hubbard and Wayne Shorter, Woody Shaw, Billy Harper, Wynton Marsalis, Horace Silver, Bobby Timmons, Cedar Walton…the list goes on and on and on. Blakey’s Hard Bop fingerprints are on an almost unbelievable amount of 20th century American music. He played with everyone – Charlie Parker, Dizzy, Miles, Coltrane, Monk, Bud Powell…and for 30-some years, he really never made a bad record. His live 80s sets are proof! He was still swingin’ to the end – he was even on The Cosby Show!

Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers’ original records still command high prices on Ebay today – because the music was so incredible and timeless.

We say Happy Birthday to the man they called Bu (short for Buhaina) who’s music we love so much by sharing some of our favorites from throughout his career. HBD!

(1947 – Blakey on drums for the original recording!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uPyJLRFk_UY

(1954 – w/ Blakey on Drums!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QhFDVFyIPeY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHCrgjsAFvU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iO6f44u0LoA&list=PL1RAEP0TAe1whophHQ9goE2sWWMnL0YcB

(Miles’ 2nd Great Quintet, with Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams)

It’s MilesMonday.

The KTRU Sunday Jazz Team are certified Miles fanatics.

And we’ve been bumping a lot of the great live 60’s recordings on Columbia lately.

People tend to gloss over this period for Miles. Don’t make the same mistake. Miles’ live recordings for Columbia are some of the best live jazz records you can own. LETS MILES FOR MONDAY:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pA8alG7Y0bs&index=2&list=PLdhGk7gKuZxYZBOS3kVhKwKk1p73uNU0f

PLUS — THIS IS COMING IN OCTOBER!!!! 🙂

“The fifth volume of Columbia/Legacy’s Bootleg Series detailing the many phases of Miles Davis’ career has been announced. Freedom Jazz Dance: The Bootleg Series Vol. 5 focuses on the Miles Davis Quintet’s work from 1966-68. At the time, the band was composed of Davis on trumpet, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, Wayne Shorter on tenor saxophone, and Tony Williams on bass. Freedom Jazz Dance is out October 21.

The 3xCD box set includes performances from 1967’s Miles Smiles, 1968’s Nefertiti, and 1976’s Water Babies (which was recorded in 1967), as well as full session reels from Miles Smilescomprising “every second of music and dialogue.” Overall, there’s more than two hours of previously unreleased material, according to The New York Times.” (Pitchfork)

The YouTube playlist for our 7/3 show is up! Get it HERE.

“Twelve voices, 30-instrument big band from Detroit in modernist, self-determining stance. Notables include vocalist Kim Weston; saxophonists Lou Barnett, Ted Buckner, Ted Harris Jr, Ernie Rodgers, Charlie Gabriel, and Miller Brisker; trumpeters Herbie Williams and Eddie Jones; trombonists Jimmy Wilkins and Phil Ranelin; bassist Duke Billingslea.” (AMG)

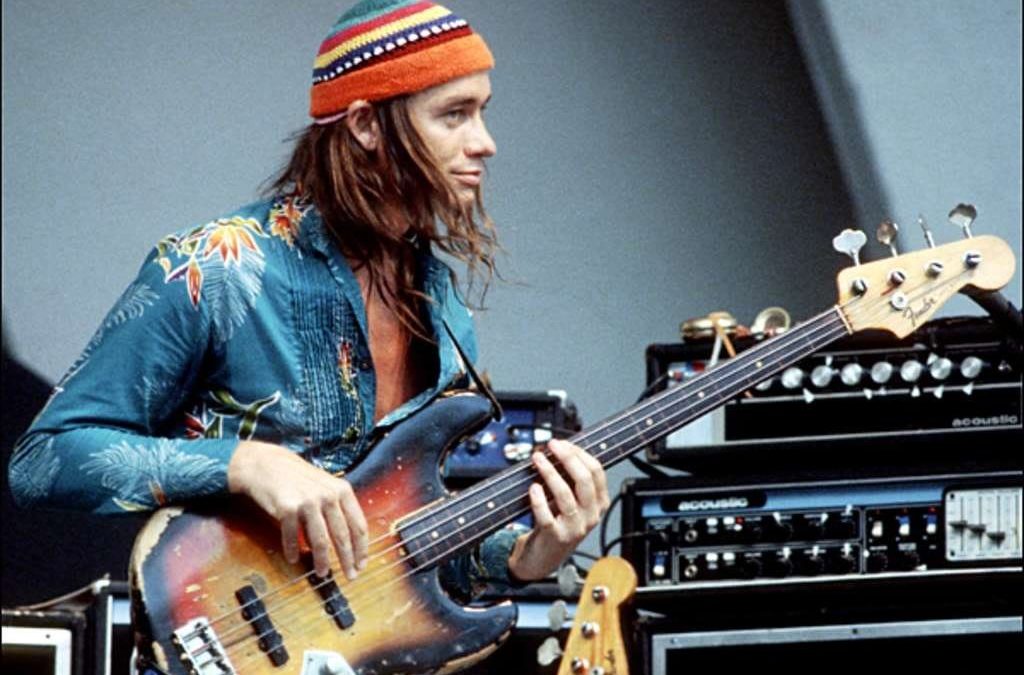

We played a couple of classic Jaco Pastorius cuts because we finally caught the doc “Jaco” streaming on Netflix. While not terribly groundbreaking it does do a good job of telling the story of one of Jazz’s most popular and beloved cult figures, a player many believe to be the best of his generation.

Check out the trailer below: