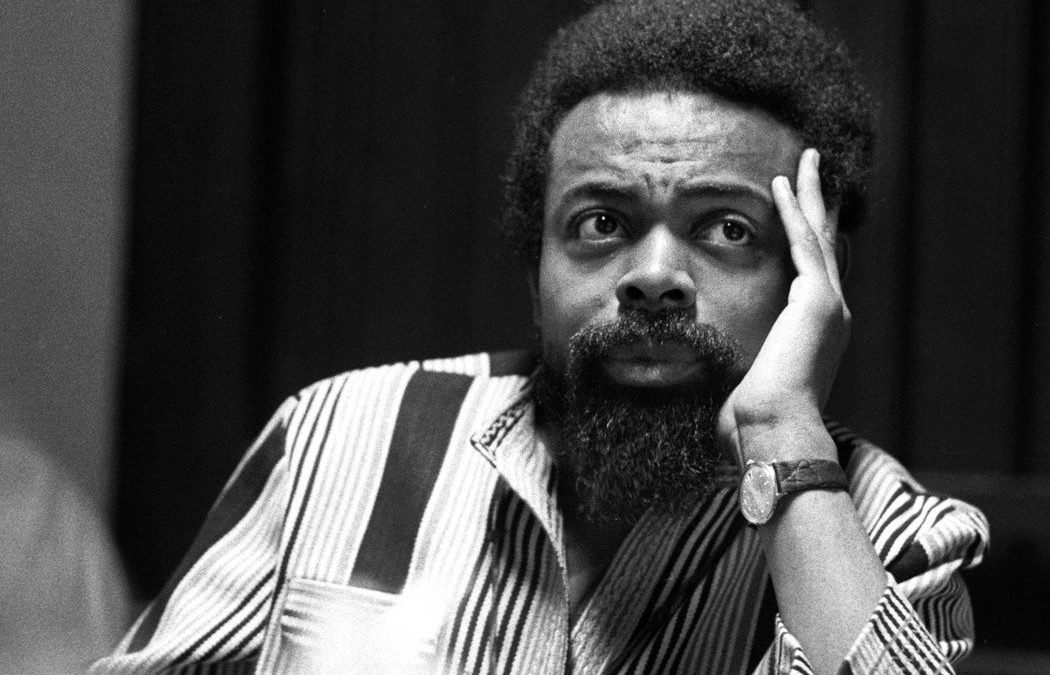

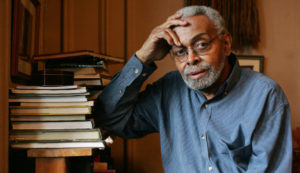

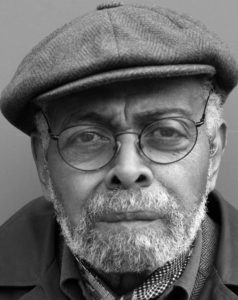

(Amiri Baraka: poet, author, historian and music critic)

The essay below was found in a blogpost from Open Sky Jazz. We are unsure of where it was originally published. In an attempt to share exciting and thought-provoking content furthering discussions on this music we love, the KTRU Sunday Jazz team will continue to share the good stuff we find and enjoy from the web and beyond. We have added pictures and numerous links to songs and visual aids to add to the experience of the piece. Click on the links! And enjoy.

What Amiri Baraka Taught Me About Thelonious Monk

(Thelonious Monk at the piano)

"Monk was my main man." - Amiri Baraka

I just spent the past fourteen years of my life researching and writing a biography of pianist/composer Thelonious Monk, and over thirty years attempting to play his music. My obsession with Monk can be traced back to many things and many people, but paramount among them is Amiri Baraka. Let me explain.

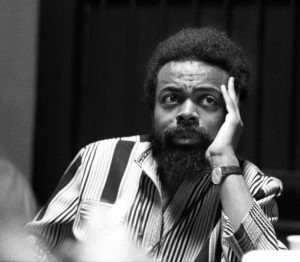

My path to "jazz" began like so many others of my generation who came of age in the late 1970s — with the funky commercial fusions of Grover Washington, Jr., Bob James, Patrice Rushen, Earl Klugh, Ronnie Laws, through Stanley Clarke and Chick Corea. But inexplicably, at the tender age of seventeen or eighteen I took a giant leap directly into the so-called "avant-garde", or the New Thing. By 1980, the New Thing wasn’t so new (and as Baraka and others have shown us, it wasn’t so new in the 1960s), but the music appealed to my rebellious attitude, my faux sense of sophistication, and to the way I heard the piano. As a young neophyte piano player and sometimes bassist, my heroes became Cecil Taylor, Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Archie Shepp, late ‘Trane, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, those cats. I knew almost nothing about bebop, nor could I name anyone in Ellington’s orchestra except for Duke. I just thought free jazz was the beginning and end of all "real" music. My stepfather introduced me to Charlie Parker, Monk, Bud Powell, Dexter Gordon, but I wasn’t yet ready to fully appreciate bebop. Then in one of my many excursions to "Acres and Acres of Books" in Long Beach, California, I picked up two used paperbacks by one LeRoi Jones: Blues People and Black Music.

I dove into Black Music first. Imagine my surprise when I discovered a thoughtful piece on Monk in a book that I understood then to be a collection of essays primarily about the "New Thing." Don’t get me wrong; I dug Monk from the first listen. I had heard an LP recorded live at the Five Spot Cafe with Monk and tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin. I wore it out, especially their rendition of Monk’s "Evidence". But Monk wasn’t part of the jazz avant-garde. He was already an old man when Ornette Coleman made his debut, or so I thought. Baraka’s Black Music corrected me, schooling me on the roots and branches of free jazz. Between his piece on "Recent Monk," his brilliant treatise, "The Changing Same (R&B and the New Black Music)," and several other pieces on white critics and the jazz avant-garde, I began to hear Monk and "free jazz" quite differently. It was Baraka who dubbed the jazz avant-garde the "New Black Music," insisting that it emerged directly out of a Black tradition, bebop, as opposed to the Third Stream experiements of Gunther Schuller, Lee Konitz, and Lennie Tristano. While Black musicians might have milked Western classical traditions for definitions and solutions to the "engineering" problems of contemporary jazz, Europe is not the source. "[J]azz and blues," he writes, "are Western musics; products of an Afro-American culture."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZZwKtBLO-zw

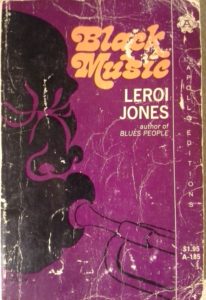

Of the few hundred times I listened to Monk, Johnny Griffin, drummer Roy Haynes, and bassist Ahmed Abdul-Malik tear the roof off the Five Spot, I probably heard Baraka, shouting his approval and urging them on from his table near the bandstand. It was August of 1958 and Baraka (when he was still LeRoi Jones) had been an East Village resident for the past year. He became a Five Spot regular when Coltrane was with Monk in the summer and fall of 1957. His constant presence gave him unique insights into Monk’s music and the challenges it created for the musicians who played with him. Indeed, Baraka was one of the few critics to admit that "opening night [Coltrane] was struggling with all the tunes." Baraka just didn’t come to dig the music, he studied Monk.

((L-R: Thelonious Monk, Jewels Colomby(?), TS Monk, Amiri Baraka (taking picture) and Ran Blake))

In fact, he was arguably the first American critic, along with Martin Williams, to really understand what Monk was doing and why a new generation of self-described avant-garde musicians was drawn to Monk’s music and his ideas. By the time Baraka entered the fray, most critics had either dismissed Monk for having no technique or formal training as a pianist, or they praised him for his eccentricity and inventiveness precisely for his lack of technique or formal training. For Baraka, the whole issue of Monk’s technique was nonsense: "I want to explain technical so as not to be confused with people who think that Thelonious Monk is ‘a fine pianist, but limited technically.’ But by technical, I mean more specifically being able to use what important ideas are contained in the residue of history or in the now-swell of living. For instance, to be able to double time Liszt piano pieces might help one become a musician, but it will not make a man aware of the fact that Monk was a greater composer than Liszt. And it is the consciousness, on whatever level, of facts, ideas, etc., like this that are the most important parts of technique."

While Baraka’s fellow Beat generation writers embraced Monk because they heard spontaneous, instinctual feeling and emotion as opposed to intellect, Baraka saw no such opposition; he was careful not to divorce consciousness and intellect from emotion. He writes, "The roots, blues and bop, are emotion. The technique, the ideas, the way of handling the emotion. And this does not leave out the consideration that certainly there is pure intellect that can come out of the emotional experience and the rawest emotions that can proceed from the ideal apprehension of any hypothesis." Like his insights about Monk’s technique, the point underscored Baraka’s general claim that bebop was roots music, no matter how deep the imperative for experimentation, because it carries deep emotions, historical and personal. The music of the Blues People.

(Baraka)

And if Thelonious Monk was anything, he was Blues People. Born in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the grandson of enslaved Africans, delivered by a midwife who was thirteen when Emancipation Day came, Monk was raised by parents who grew up picking cotton and survived on odd jobs and cleaning white folks’ homes. His mother brought Thelonious and his two siblings to New York in search of a better life, and while they enjoyed more opportunities the Monks settled in the poor, predominantly black neighborhood of San Juan Hill (West 63rd Street, Manhattan). Thelonious grew up listening to the blues, jazz, the rhythms of calypso and merengue, hymns and gospel music (he spent two years traveling through the Midwest with an evangelist). His mother Barbara, scrubbed floors to pay for his classical piano lessons, and Monk continued his studies under the tutelage of the great Harlem stride pianists of the day. Monk told pianist Billy Taylor "that Willie "The Lion’ and those guys that had shown him respect had… ’empowered’ him… to do his own thing. That he could do it and that his thing is worth doing. It doesn’t sound like Tatum. It doesn’t sound like Willie ‘The Lion’. It doesn’t sound like anybody but Monk and this is what he wanted to do. He had the confidence. The way that he does those things is the way he wanted to do them."

Willie ‘The Lion’ never mentions Thelonious in his memoirs, but he described the all-night cutting sessions which sharpened Monk’s piano skills: "Sometimes we got carving battles going that would last for four or five hours. Here’s how these bashes worked: the Lion would pound the keys for a mess of choruses and then shout to the next in line, ‘Well, all right, take it from there,’ and each tickler would take his turn, trying to improve on a melody… We would embroider the melodies with our own original ideas and try to develop patterns that had more originality than those played before us. Sometimes it was just a question as to who could think up the most patterns within a given tune. It was pure improvisation." A later generation of bebop pianists would often be accused of one-handedness; their right hands flew along with melodies and improvisations, while their "weak" left hands just plunked chords. A weak left hand was one of Smith’s pet peeves among the younger bebop piano players. "Today the big problem is no one wants to work their left hand — modern jazz is full of single-handed piano players. It takes long hours of practice and concentration to perfect a good bass moving with the left hand and it seems as though the younger cats have figured they can reach their destination without paying their dues."

(Willie "The Lion" Smith)

Teddy Wilson, though only five years older than Monk but considered a master tickler of the swing generation, had nothing but praise for Thelonious’s piano playing. "Thelonious Monk knew my playing very well, as well as that of Tatum, [Earl] Hines, and [Fats] Waller. He was exceedingly well-grounded in the piano players who preceded him, adding his own originality to a very sound foundation." Indeed, it was this very foundation that exposed him to techniques and aesthetic principles that would become essential qualities of his own music. He heard players "bend" nots on the piano, or turn the beat around (the bass note on the one and three might be reversed to two and four, either accidentally or deliberately), or create dissonant harmonies with "splattered notes" and chord clusters. He heard things in those parlor rooms and basement joints that, to modern ears, sounded avant-garde. They loved to disorient listeners, to displace the rhythm by playing in front or behind the beat, to produce surprising sounds that can throw listeners momentarily off track. Monk embraced these elements in his own playing and exaggerated them.

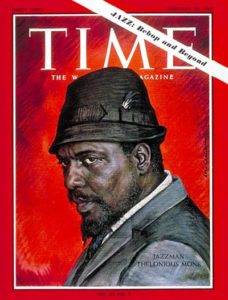

Finally, Baraka was one of the first critics to predict that Monk’s long awaited success in the early 1960s might negatively impact his music. Indeed, this was the point of his essay, "Recent Monk." Thelonious’s fan base had expanded considerably after he signed with Columbia Records, made a couple of international tours, and appeared on the cover of Time Magazine in 1964. But Baraka noted that Monk’s quartet, like so many successful groups, began to fall into a routine that sometimes dulled the band’s sense of adventure. Baraka warned, "once [an artist] had made it safely to the ‘top,’ [he] either stopped putting out or began to imitate himself so dreadfully that early records began to have more value than new records or in-person appearances… So Monk, someone might think taking a quick glance, has really been set up for something bad to happen to his playing." To some degree, Baraka thought this was already happening and he placed much of the blame on his sidemen. Of course, Monk hired great musicians during this period — Charlie Rouse (tenor sax), bassists Butch Warren and Larry Gales, and drummers Frankie Dunlap and Ben Riley. But the repertoire remained pretty much the same, and the fire slowly dissipated. Monk himself continued to play remarkably, but there was an element of predictability that overrode all the amazing things he was doing. "{S}ometimes," Baraka lamented, "one wishes Monk’s group wasn’t so polished and impeccable, and that he had some musicians with him who would be willing to extend themselves a little further, dig a little deeper into the music and get out there somewhere near where Monk is, and where his compositions always point to."

(Monk on the cover of TIME magazine, February, 1964)

Baraka never gave up on Monk, and while I can’t prove it I suspect Monk’s music continues to have a strong philosophical and aesthetic influence on both his literary and political work. But more than anything, I will always be grateful to Baraka for helping me discover Monk, for revealing that Monk’s rootedness in this history, in family, in tradition explains why his music, as modern as it is, can sound like it’s a century old. It explains why he always remained a stride pianist; why his repertoire was peppered with sacred classics like "Blessed Assurance" and "We’ll Understand it Better, By and By"; and why the careful listeners can hear in Monk’s whole-tone runs, forearm clusters, unusual tempos and spaces, shouts, field hollers, the rhythm of a slow moving train, rent parties, mourners, children playing stickball and marbles, and the Good Humor or Mr. Softee truck on a summer evening.

Like most scholars and other voyeurs, we are always listening for, and looking at, art for personal tragedy rather than collective memory, collective histories. Amiri Baraka understood the fallacy of this approach. Perhaps this is why he writes in the poem "Funk Lore" (one of several associated with Monk):

That’s why we are the blues

Ourselves

That’s why we

Are the

Actual

(Amiri Baraka, formerly known as Leroi Jones)

END

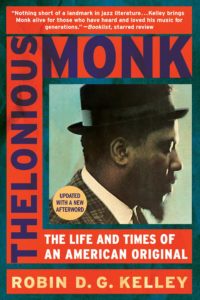

To reiterate, the piece above was written by author Robin D.G. Kelley. His biography of Thelonious Monk is a contemporary classic and is considered an essential for the jazz bookshelf by the KTRU Sunday Jazz team. The book is available at Amazon.

(Author Robin D. G. Kelley)

KTRU Sunday Jazz airs every Sunday at 2pm central on 96.1 FM Houston and live online at ktru.org.